Opinion

The Civility Of Patience

The condescending social media posts about Maratha protesters mirror the colonial tactic of 'othering'.

A famous line about protesting a dire state of things by Bertolt Brecht goes, “In the dark times, will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing. About the dark times.” The line is used mostly in the context of finding expression during oppression, but it also highlights one integral function of protest and that is the reclamation of joy and spaces by the oppressed.

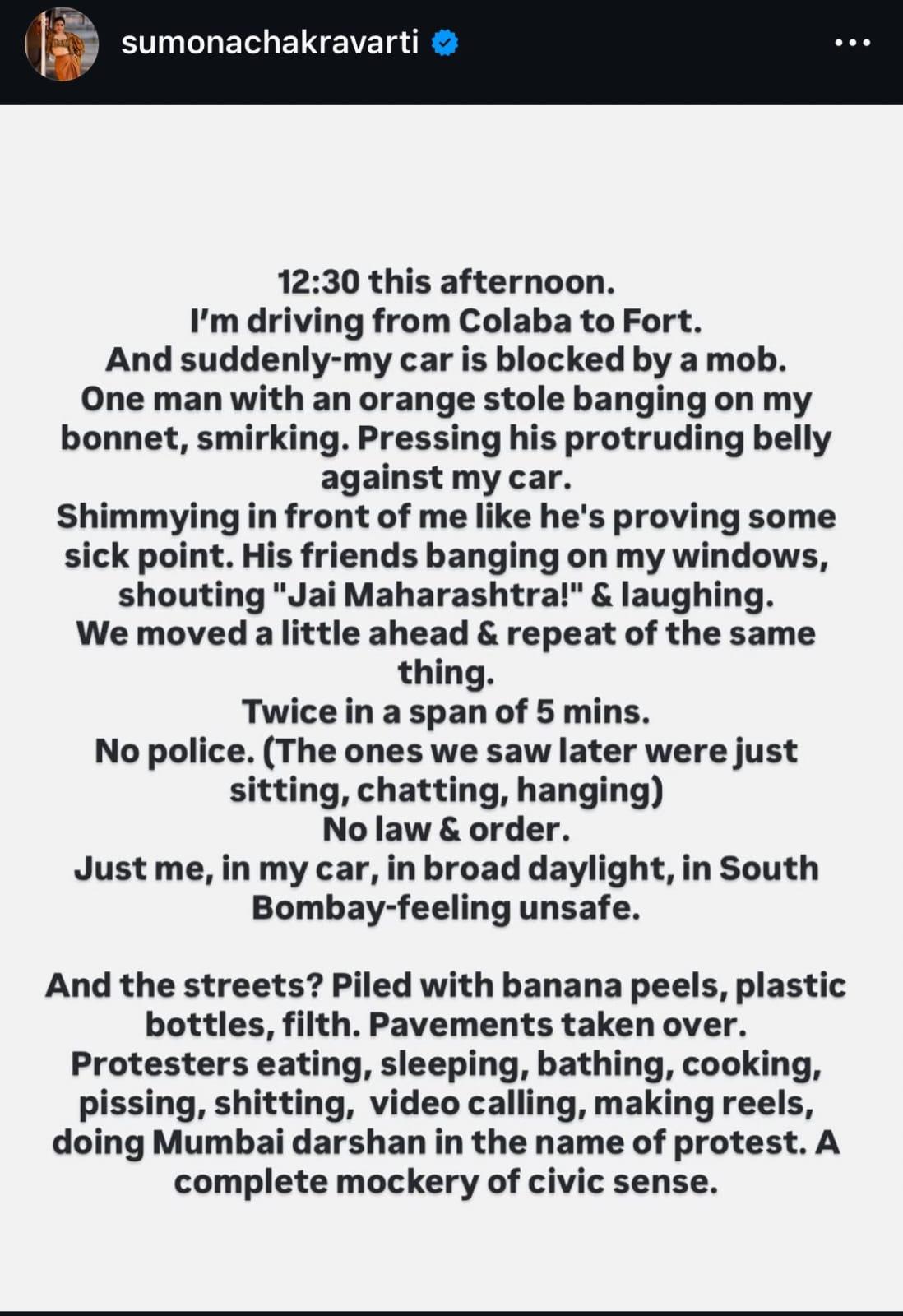

A Times of India journalist, one Ms Pinto, has made it her mission for the last few days to constantly tweet videos about the Maratha protesters, who have taken over the streets of Southern Mumbai for the last couple of days. Her tweets, if not reeking of blatant classism, display a curiosity worthy of a colonial explorer finding savages in the ‘discovered’ wilderness.

‘Maratha protesters bathing in the middle of the street’, says one of her tweets with a video attached showing a man at the ‘side’ of the road, having a bath. Another tweet mentions, ‘Maratha protesters at Marine Drive’. Another one is captioned, ‘Maratha protesters in a Westside store’.

Maratha reservation protesters playing kho-kho in Mumbai.

After receiving a reprimanding call from an activist, Ms Pinto takes shelter behind the fact that her tweets had no mention of any ill will towards the Maratha protesters. Which well might even be true. But what she omits from here, is also the fact that sometimes much is said about something when nothing is said.

Even if one assigns sheer curiosity to her tweets, what level of disconnect does one need to have from the conditions of people living not very far from them, to have their curiosity be so condescending? What curiosity does she find in a protester with a saffron printed Maharashtrian cap and muffler entering an air-conditioned Westside store? What triggers such a sense of wonder in her as to find this otherworldly enough to make a series of tweets about it?

Not just this Anglo journalist, but a myriad of twitterati accounts have suddenly found ‘their’ city being ‘invaded’ by these ‘gross’, ‘uncivilised’, ‘dirty’, village folk. They underline and underline again, how the ‘financial capital’ of the country has been taken hostage by people, who according to their limited understanding of the world, contribute nothing at all to that wealth and prosperity.

A very popular Marathi joke about the urban elites of Pune portrays a youngster from the city being asked in the classroom, ‘Where does Milk come from?’ and the child says, ‘Chitale!’ (a popular marathi milk brand). The naive disconnect of the Mumbai elite is very similar to that of the child. They too think that their daily fresh vegetables, milk and groceries come, not from the farms and dairies run by the same rural savages, but from the brands that deliver them. It might be quite a visual to imagine a creature called Amul with teats pumping milk into the streets of Mumbai.

Yes, Mumbai. The urban elite ‘refuse’ to call it Mumbai, sticking to Bombay as if the name will take them back to the romanticised past where the city does not belong to the Machchiwali, Kaamwali or the Dabbawalla, but only to the Bureaucrat, Technocrat and the Business tycoon sitting in a restaurant watching cabaret sipping a scotch on the rocks.

Frantz Fanon, in 'Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth', argues that colonial power structures rely on dehumanising the colonised, portraying them as inferior or disruptive to justify control. The condescending social media posts about Maratha protesters mirror this colonial tactic of 'othering', where the protesters are framed as out-of-place or uncivilised for asserting their rights in their own state.

This attitude reflects a lingering colonial mindset among "outsiders" who view the Marathas' presence or demands as illegitimate. Fanon’s concept of the colonised reclaiming their agency through resistance is relevant here, as the Maratha protests represent a demand for recognition and rights within their own socio-political space.

It also invisibilises the long existence of the natives of the Mumbai isles on whose erasure the modern myth of Bombay was built.

Mumbai has long been a point of contention for the non-Marathi elite and the native Marathi working class. The claim has always been that which echoes the claims the Zionists make about Palestine. “There was nothing on this land until we came,” they say to credit themselves with not just the discovery of the land, but its creation itself. As if the native Kolis, Pathare Prabhus, Packalshis, Bhandaris and other Marathi communities were merely savage squatters until the Portuguese and the British taught them civilisation and the Baniya capitalist made the land rich.

Not only does this just deny the role of labour in creation of wealth, but it also invisibilises the long existence of the natives of the Mumbai isles on whose erasure the modern myth of Bombay was built. Maharashtra, especially the working class of Maharashtra, fought tooth and nail to keep its claim to this land of theirs and some 106 people were martyred for the land to remain Marathi.

In recent times, Mumbai especially has seen linguistic tensions flare up and the issue of migration come to the fore. While the national media portrayed each incident of confrontation with the locals and some or the other Hindi speaker as an evidence of xenophobia and quasi genocide itself, not one liberal progressive mind speaking to the nation bothered to raise a voice for the Marathi native facing discrimination over food, language and class from Mumbai’s elites. Not one of them attempted to understand why the similarly underprivileged worker from Maharashtra’s rural areas has limited access to Mumbai, many of whom can merely dream of occupying its spaces.

आता मराठ्यांनी मुंबई च्या वातावरणात कस जुळवायचं शिकत आहेत...आता मागे हटणार नाहीत.#MarathaReservationProtest #maratha_reservation #MarathaInMumbai pic.twitter.com/q7mfETfhSj

— Yashawant pawle (@yashwant_pawle) August 31, 2025

The Maratha protesters in Mumbai, after years of this erasure, have claimed a space almost denied to them, even when its existence and function comes at their expense. Some reports suggest that the ‘Metropolises’ of Mumbai, Thane, Pune alone suck more than half of the water and electric resources from the state of Maharashtra. While the farmers risk lives in their farms at midnight thanks to the electric supply policies, urban spaces and businesses light-up throughout the day with not a single touch of guilt. During the period of some six months of 2025, at least eight farmers died by suicide every day! This, in a fairer world, would have called at least for introspection if not for punishment.

And evidently, we do not live in a fair world. Which is why, it becomes important for the oppressed and the invisibilised to grab justice that is kept away from them. The poor in this country, even after facing endless travesties, have not chosen the path of violence against the insensitive rich. That itself is the testament of their civility.

There are several critical approaches with which one can look at the demands of the Maratha protests. The demand for reservations for an issue which is deeply rooted in economic factors can and must be critiqued through academic and procedural methods. But the condescension from a colonising lens which denies the citizen of this land the access to the resources that they share with you, is a testament to your uncivil nature.

May it be the Farmers protesting in Delhi, or now in the ‘Financial Capital’, the disdain towards farmers, and protesters in general, reflects nothing but the chasm between the urban spaces and the rural mind. The images of these farmers, mostly from the dry and arid hinterland of Marathwada and South-Eastern Maharashtra enjoying the spectacle of the sea, playing kho-kho on the street outside the CSTM station or having a stroll through an air-conditioned shopping store, converting these sanitised and commercialised spaces into public ones, should have actually been celebrated as visuals of the true reclamation of a space, that of the people, by its people. But to the uncivil colonising mind, it shall not appear so.