Opinion

A nobody's story of Nehru

The first Indian PM went through a series of re-tellings in my memory.

Jawaharlal Nehru, always the enigma, might as well be the most surreal figure in Indian politics since Independence. India's first prime minister, has been documented, written about and discussed in almost all the ways possible, even more at times, than his ideological mentor, M.K Gandhi. But for a person who has no academic overbearing, Nehru is a myth, that has unfolded over the past few decades, from the beloved freedom fighter with rosy cheeks, to the 'promiscuous' western liberal, who supposedly ruined India.

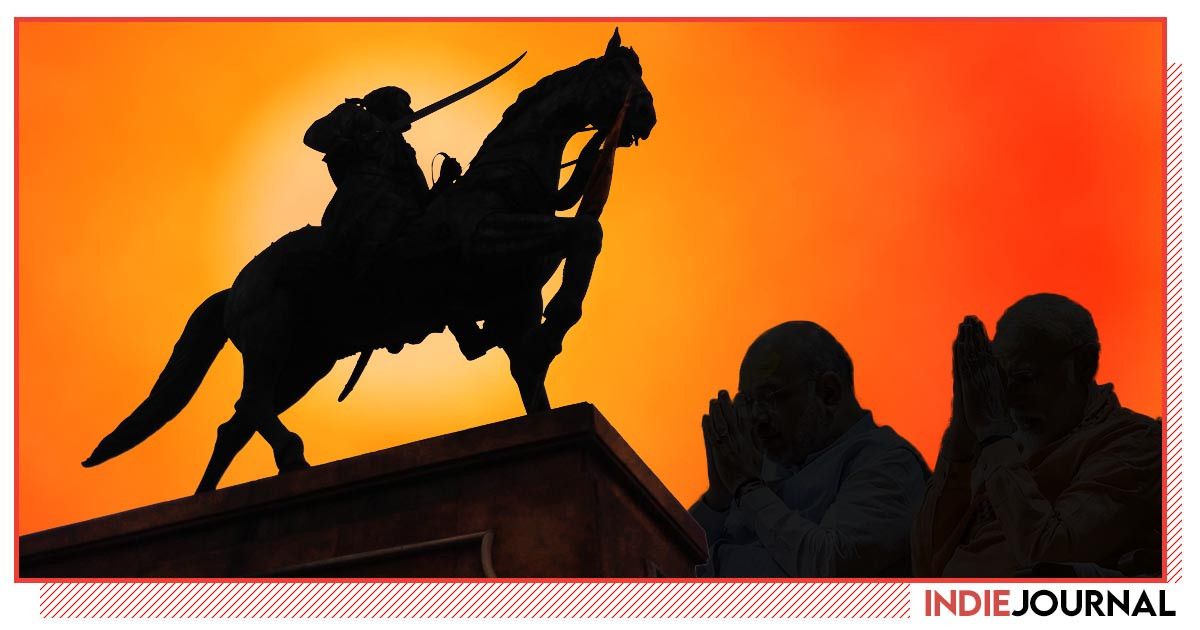

Growing up in a small village in Maharashtra, Nehru was ubiquitous. He was present in the Zilla Parishad school as a mural painted on the walls, in the Gram Panchayat building as a photo frame and he had even crossed the border between the mortal and the immortal and smiled at me from a photo framed right next to the various hindu gods and Chattrapati Shivaji, the legendary medieval king who holds sway over Maharashtra. I grew up looking at him as the gentle figure, the beloved 'Chacha', remembering, and more importantly, perceiving, him as India's first prime minister only after the question appeared in several general knowledge exams.

Old people in villages, tell many a stories and anecdotes. Maharashtra, was one of the states most influenced by the Congress movement. Even today, though facing electoral routs, one after the other, the Congress has members, supporters and participants from most Marathi families. I remember one elder in the village telling those around him a vivid memory of seeing Nehru. "Nehru had come to Sangli (the nearest major city and an old Congress stronghold) for a 'sabha'. He was going to give a speech. We had thronged to the city, going by the hundreds on bullock carts. I saw him stand on the stage, wearing his trademark jacket," He narrated, almost romantic about it, adding "He had cheeks as rosy as a Kashmiri apple."

With time, Nehru, the hero, began to appear only in the textbooks of history, as a dry, linear and a typically bureaucratic narration. He appeared as a statesman, with no wars that he fought or led, no heroic deed to be role-played on the school stage and no song or paen sung about him. He started to become boring and mostly took place in the mind of me as I entered youth, as a sarkari babu at most. Nehru, devoid of his charm, his attitude and his values, became a compulsion that one had to come across in the curriculum.

Nehru, though immensely popular, had a difficult history with Maharashtra. One of the most significant of his trysts with the state, might have been when the state was undergoing the Sanyukt Maharashtra (United Maharashtra) movement. Most of Maharashtra, was part of the Bombay province along Gujarat. Mumbai, then Bombay, was a city with millions belonging to the working class which was mostly Marathi speaking and with elite Gujarati businessmen and industrialists who owned the capital and resources. As states began forming on linguistic bases, there was a demand that Mumbai, be a part of Maharashtra. The Congress leadership then, favoured the capitalist-industrialist control of the city. The Marathi working class felt betrayed. Nehru, is said to have shown black flags when he reached Pratapgad, to inaugurate a statue of Shivaji.

As the air changed in the state over the last two decades, the narrative shifted from the national movement to the Marathi identity and pride. The national heroes were almost discarded in the public sentiment and a regional aspiration harking back on the heroics of Shivaji, whose empire stretching almost pan-India has been an object of pride for the Marathi people. Nehru, now, began to look like a antagonist in my mind, who had been unfair to the Marathi people and their history and this is where the new narration of Nehru began to make ways in the perception of memory.

Reading material, gossip, debates, turned to Nehru as a 'failed leader', a 'malicious dictator' and 'sexual deviant' and a 'Socialist'. The newly accessible internet and bluetooth technologies were full of interesting gossip and photographs of Nehru with Edwina Mountbatten or in proximity of fair skinned women, having a smoke while at it. A certain sense of injustice and insult to 'our' language and state was converted in anger for Nehru, the Congress and all the values that is supposedly stood for. Nehru, had become the reason of almost every shortcoming, that a frustrated youth was facing as a result of his times. Jobs, national pride, a sense of stagnancy, rising aspirations, everything centered around a sense of historical injustice.

Gradually, with a better understanding of the world and history, I overcame the narratives that had been spread around me about what or who Nehru really was. Narratives, not facts, shape perspectives of memory. To think of it, it was not as much a fault of Nehru's as it was of his successors, of glorifying him to the extent that he looked like a monolith in the pantheon of leaders that won us the freedom struggle. It was because it appeared that Nehru, along Gandhi, was to be credited for every win, that it became possible to blame them for each failure too. The Indian state machinery's failures, became their personal failures.

Even today, as Congress struggles with the constant attack on the Nehru-Gandhi legacy, it must introspect rather than just blame the right wing forces. If it had been honest to the values that the behemoths of Indian polity has espoused and symbolised, if the Congress had been as much a Nehruvian or Gandhian itself as it wants people to believe it is, if it had delivered the tryst with destiny that Nehru had envisioned, just so, it would not have been possible for anyone to make Nehru a soft target, decades after his death.