Quick Reads

Unrepresented histories are unfair to the sacrifices of those like Umaji Naik

In 1831 Umaji wrote a Manifesto of Independence.

Suraj Shankar Jadhav | As we embrace the 75th anniversary of our Independence, we must explore events and people who are missing out on our national narrative of Independence. The Indian Independence movement does not have an exact starting point. Why is Independence meant to be only from the British and not from the social elements which still abuse and have kept a considerable population under its heels?

Some groups and communities in India still claim to be under foreign rule and authority. Independence is yet to reach them. Dr. BR Ambedkar elaborated on prioritising social freedom before political freedom. He tried his best and his words in 'Annihilation of Caste' still make sense. This anecdote allows us to define Independence as a fluid term rather than a concept with a solid start and definite end. Not to take away anything from the mainstream movement and sacrifices or the sacredness of the Indian independence movement, but this article is about where the idea of Independence would have started and how we should reclaim the neglected part of its history.

The beginning of the 19th Century was not a celebrated period for empires and rulers in India. As most of them were falling apart under British rule and mostly performing the roles of the namesake, just so that the hierarchy-friendly population of Indian terrain would not feel bad and, most importantly, that they would not revolt. The same happened in the case of the Maratha kingdom on the Deccan plateau, which is most of the current state of Maharashtra. The Peshwai in many ways abused the immense efforts of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj had taken to establish the Maratha empire; these accounts are spread over numerous texts.

The same happened in the case of the Maratha kingdom on the Deccan plateau.

When the British took control of Pune, they had to reorganise. In course of this process, they took away the livelihood of multiple small tribes and groups who were traditionally employed by the Maratha kingdom and Peshwai had no option but to comply because they had no option. Their heightened caste consciousness towards the oppressed was not of caring nature, unlike Shivaji Maharaj. One such community was the Ramoshi community, traditional gatekeepers for the Purandar fort. These changes took place after 1803, and the community was left without any source of livelihood.

Members of the Ramoshi community were traditionally employed as 'Rakhwaldar's' in villages. With the advent of the British community, that too changed. During this takeover of Purandar fort, Umaji must have been in his adolescence. He saw what happened to his community and how they were thrown out of their home and resources. Let's look at how he developed and his activities in the later part of his life. We can assume the takeover of Purandar fort must have had a significant impact on his psyche.

Portrait of a Berad/Ramoshi man.

The commune spread out across different landscapes. Some families employed themselves as local landlords, and some who were quite rebellious chose to explore new opportunities in the nearby territory. As Umaji grew up, he started moving around the region, searching for youths from the Ramoshi community. His initial sense of independency was primarily dominated by securing a livelihood. After spending some years as a dacoit, troubling British forces and facing the brutality of British administration, Umaji decided to turn his attempts into an organised fight.

Umaji was a devotee of the rural god Khandoba. He, with several accomplices, pledged to dismantle the British empire at the same temple. In his later years of rule, he used the Khandoba temple as his capital or the centre of his activities. On one of his expeditions around 1817, he was caught and jailed by British authorities.

This became a turning point in Umaji's life and it is of significant influence on the idea of India's stature. Mahatma Jyotiba Phule was yet to be born; Shaniwarwada was yet to burn down and Dalits were still humiliated on the streets with the broom at their waist and pot on their neck. Aside from being invisible, most of the tribal groups were yet to be Sanskritised. Ahom dynasty was still fierce enough to keep the British out of their way, the Maratha empire which spread across the south Indian region was coming to an end. Amid all of this, Umaji learned to read and write during his stay in prison. For someone who was called and acted as a dacoit, Umaji turned the punishment into a learning opportunity.

Umaji turned the punishment into a learning opportunity.

Since out in 1818, Umaji amplified his efforts against the British rulers. After realizing that Umaji is an asset too good to lose, Britishers employed him in their administration. Groups like Umaji's caused the administration quite trouble mostly through organised robberies and creating unrest. They were difficult to track, they knew the terrain better than any officer in British ranks. So the British did what they were good at; negotiation.

It was like making the most notorious kid the class monitor. There is a risk factor in negotiation; either the kid will discipline the class or take the mess to another level. In the case of Umaji, the latter came true. Umaji’s strong belief against invaders never turned him into an obedient pet. He used this opportunity to build funds that could be utilised against his employees in the future. This arrangement was on and off a couple of times. There came a point where Umaji realised there were hefty of individuals from his community who might and were negotiating with the British on the same line as his, and there always be an alternative.

A full-fledged rebellion was declared against the British. Umaji received support from the villages nearby Jejuri. In no time, it spread around Bhor and Saswad regions; all of these surrounded the Pune region. Captain Alexander Mackintosh was given the responsibility to bring in Umaji. A bounty of 10,000 rupees and 400 bighas of land was declared for the same. His spread-out spy network, his knowledge about nooks and corners of every hill in the region and support from the villagers made it quite tricky for Captain Mackintosh to keep track of him, let aside bringing him in.

Umaji declared himself as a king and started ruling the Jejuri region.

Not a surprise as Bahirji Naik, head of the Shivaji Maharaj’s spy network, came from the Ramoshi community. So guerrilla warfare was not foreign for Umaji too. Umaji declared himself as a king and started ruling the Jejuri region. He would assemble with his ministers at the temple of Jejuri and carry out the affairs of the state. Except for the vision and support of the villages, Umaji never had a throne or the luxury which we relate with the idea of a King.

A couple of hundreds of warriors wandered around hills, sometimes eating once or twice a week, sleeping under the shade of the moon. They knew no families or kinship. They loved their freedom so much that they were standing against the most brutal colonial force the world had ever seen. He looted several British treasuries and distributed them amongst the population. As much as he was feared by the British, it was no way compared to what landlords and village heads in his region felt.

Umaji became Umajiraje. ‘Raje’ means the king. To put his claim as king and warn the British about their activities, he decided to articulate his stance.

In 1831 Umaji wrote a Manifesto of Independence and declared war with and independence from the British empire. The manifesto appealed to kill any British in sight, leave British employments, loot their treasuries and urged his fellow countrymen to uprise from all corners of the country and make it hell for British forces. It was declared that the new administration will punish the ones who don’t obey these orders. This manifesto was a red alert for the East India Company and Captain Mackintosh. The 1857 mutiny was still 26 years away and the formation of congress was another half a century away. Umaji's effort might have been minuscule, but he was a visionary. His perception and spark of the idea of freedom might not go along with academic definitions, yet, he did write the Manifesto of Independence.

.jpg)

Mutinous Sepoys, c. 1857. Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London. Accession no. NAM 1971-02-33-495-22. Described on the museum website as "Coloured lithograph from 'The Campaign in India 1857-58,' a series of 26 coloured lithographs by William Simpson, E. Walker and others, after G. F. Atkinson, published by Day and Son, 1857-1858."

Later, in 1831, he was given away by one from his close circle and imprisoned at Pune. A court procedure was followed and the death penalty was declared on him. He was hanged on February 3, 1832, at the current Khadakmal Police station in Pune. He was hanged to a tree, and his body was kept there for three days to instill fear amongst anyone trying to pursue the same path as him. Umaji was the first to be given the judicial death penalty for perceiving the idea of an Independent India. He is regarded as ‘Adya-Krantiveer,’ the one who came before everyone.

The history of independent India is at a juncture where it is treated more as a threat than a source of knowledge. There’s a famous saying, ‘History is written by the winners', but it is also written by the ones who have the capacity and the resources to accumulate cultural capital. So the most significant part of History glorifies and maintains the status quo of the rulers. Appropriation of History is problematic and so is neglect. Neglect of any kind is defined as abuse and we might say that neglected histories represent the historical abuse of the groups and communities which played their part in the Indian Independence movement.

Appropriation of History is problematic and so is neglect.

By ignoring and not appreciating their roles, the system removes the chance of enlightenment for the same communities. The still-existing Habitual Offenders Act is a real example of the same. De-notified communities included in Criminal Tribes Act still suffer the brunt of the stigma of criminality. The Ramoshi community is one of them and so many others. Orientalism has been much criticised on the part of westerners. Yet, we forget that these ideas were sustained and supported by the ruling communities of India for centuries. British brought the Criminal Tribes Act, but it was sedentary communities who made sure of its implementation. Academicians giving battle cry on orientalism might take some time out to write a word or two about the brutality of Habitual Offenders Act.

Captain Alexander Mackintosh had a duty to perform, to catch Umaji and make sure he didn’t turn into another Shivaji. Yet the only available documentation on Umaji was done by him and archived by the California University. He wrote a full-fledged report on Umaji and interviewed him for months before he was hanged. Our failure lies not in the part where we couldn’t write it on our own but in the part where we accepted his version as it is. Mackintosh was not the only one in line to do so; orientalism had a force and so do the clergies of our time.

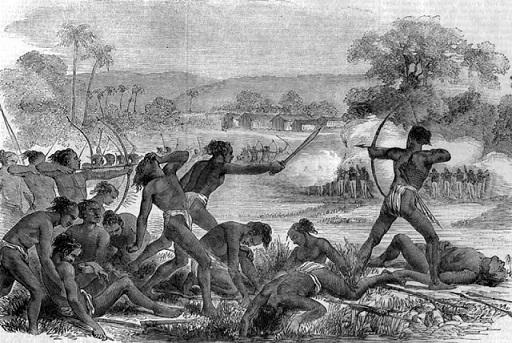

Revolt of Tilka Manjhi.

Umaji is merely a representation of what the History of independence of India might have missed. There were several on the likes of Tilka Manjhi, accounts of Sambalpur revolt, Kherwar Uprising, Santhal rebellion, Munda rebellion and rebellion of Tana Bhagat, to name a few. Ideologies are meant for the middle classes, the elites make sure that they are well fed under any governance and the oppressed have nothing to lose, neither they gained anything over these years from anyone. It takes generations of downtrodden to build enough capital so they can narrate and reclaim their histories and take pride in them.

Suraj Shankar Jadhav is a Ph.D. Research Scholar at the Pondicherry University.